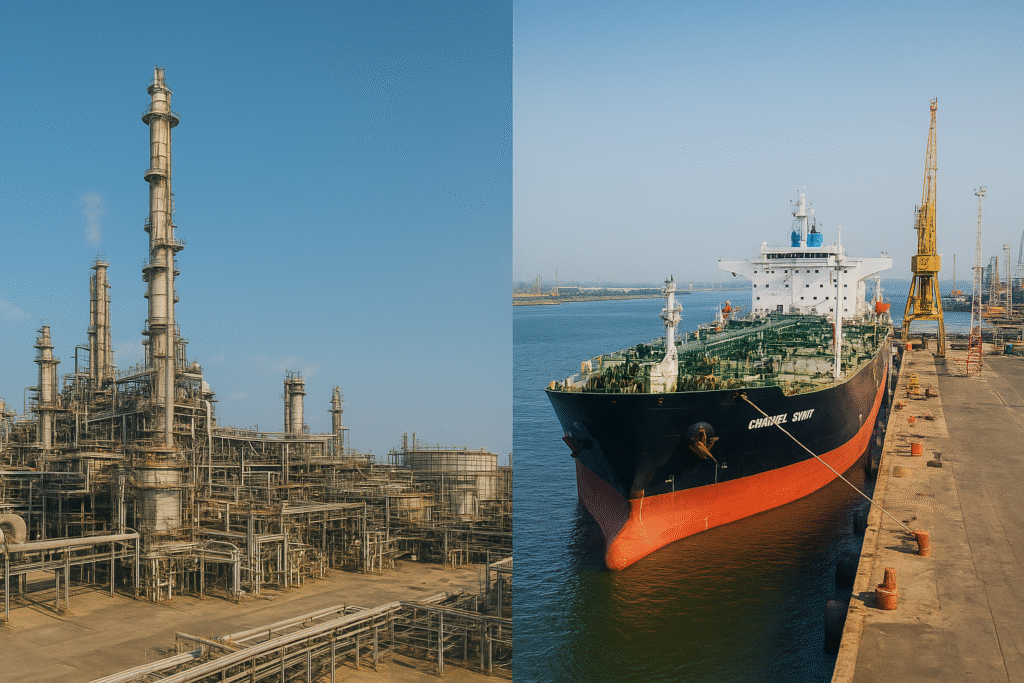

Nigeria’s downstream petroleum sector is undergoing a period of transition defined by both progress and contradiction. Despite the commissioning of the $20 billion Dangote Petroleum Refinery, Africa’s largest single-train refinery with an installed capacity of 650,000 barrels per day, the country continues to rely heavily on imported refined petroleum products. Recent industry data indicate that between October 2024 and July 2025, Nigeria consumed approximately 12.5 billion litres of petrol, of which an estimated 9.08 billion litres, representing about 72.6 percent, were imported.

This outcome underscores what has become widely described as Nigeria’s fuel paradox a situation that appears contradictory but reflects the structural realities of the nation’s energy ecosystem. On one hand, Nigeria now possesses substantial refining capacity; on the other, it continues to depend on external sources to meet domestic demand. The paradox illustrates the gap between potential and performance in the country’s refining and supply chain framework.

In the first quarter of 2025, Nigeria’s petrol import bill was estimated at ₦1.76 trillion, a 54 percent decline compared to the corresponding period of 2024. For the first half of 2025, total import expenditure reached roughly ₦4.14 trillion almost half the amount recorded in the same period a year earlier. While these figures reflect a gradual improvement, they also confirm that import dependence remains significant despite ongoing domestic refining efforts.

Operational challenges continue to limit the full utilization of the Dangote Refinery’s capacity. Inconsistent feedstock supply from local producers has forced the refinery to supplement its crude oil requirements with imported barrels, constraining output destined for the domestic market. Distribution bottlenecks and logistical limitations across Nigeria’s midstream infrastructure further complicate product evacuation, resulting in inefficiencies that sustain the need for imports. Current reports suggest that domestic refineries collectively meet less than half of national daily fuel demand.

Between September and November 2024, major oil marketers sourced approximately 148 million litres of petrol from the Dangote Refinery an encouraging start, but still insufficient compared to total national consumption. By contrast, in February 2025 alone, Nigeria imported around 701 million litres of petrol and 265 million litres of diesel, at a combined cost of approximately ₦930 billion.

The macroeconomic implications of continued fuel importation are significant. Persistent import spending exerts pressure on foreign exchange reserves, undermines currency stability, and contributes to inflationary trends. Although the refinery has begun exporting refined products an estimated 1.35 billion litres of petrol were exported between June and July 2025 the balance between export earnings and domestic supply remains delicate. The refinery’s success on the international market, while commendable, highlights the need for stronger policy alignment to ensure that Nigeria’s domestic energy needs are adequately prioritized.

Government institutions and regulatory agencies are taking steps to address these structural challenges. Efforts are underway to strengthen crude-supply mechanisms to local refineries, streamline transportation and distribution systems, and establish pricing frameworks that incentivize local marketers to source domestically. These measures are expected to support gradual substitution of imported petrol with locally refined products in the medium term.

Ultimately, Nigeria’s fuel paradox encapsulates both progress and unfinished reform. The Dangote Refinery has redefined the scale of local refining and positioned the country as a potential energy hub for West Africa. Yet, the persistence of imports underscores that capacity alone is not enough; efficient feedstock allocation, coordinated infrastructure, and transparent regulatory mechanisms are essential to achieving full energy self-sufficiency.

The path forward requires sustained collaboration between government, private operators, and financial institutions to unlock the full potential of Nigeria’s refining industry. As these elements converge, the paradox will give way to progress transforming Nigeria from a net importer of refined fuel into a self-sufficient and export-oriented energy economy.